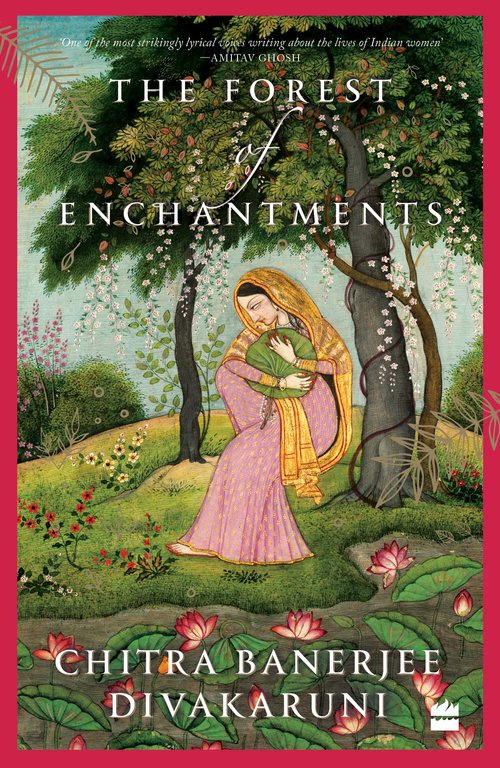

Book Review: The Forest of Enchantments

Reviewed by Ananya Sarkar

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

The Forest of Enchantments

Harper Collins Publishers India, 2019

ISBN 978-93-5302-598-4

Pages 359 Price Rs 599

Tale of Sita as a Path-Breaker

“Sita’s story haunted me,” confesses Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni in the Author’s Note of The Forest of Enchantments, “Because it was one of the first stories I was told, and because I sensed there was a disconnect between the truth of Sita and the way Indian popular culture thought of her. I sensed that Sita was more than what we took her to be.” And so, in her latest novel Divakaruni explores Sita’s story with new insight, starting with the known and familiar and then examining uncharted possibilities. Creativity, imagination and extensive research (from the Valmiki Ramayan, Adbhuta Ramayan, Kamba Ramayan and Bengali Krittibasi Ramayan) come together in The Forest of Enchantments to create the perfect amalgam. Placing Sita at the centre of the novel and presenting her version of the Ramayan, the author essentially presents to us the Sitayan.

The story begins at the point where Sita is living with her young boys, Lav and Kush in Sage Valmiki’s ashram. Valmiki has been busy writing the Ramayan on Ram’s adventures as hero and king. When it is complete, with due respect the sage hands it over to Sita for review. He wants her to be the first to read it as it is her story too. Sita, however, angrily points out that it does not embody her story in totality. When Valmiki says that he wrote whatever was revealed to him in divine vision, she drily replies, “It must have been a god that brought it to you then, and not a goddess. For you haven’t understood a woman’s life, the heartbreak at the core of her joys, her unexpected alliances and desires, her negotiations where, in the hope of keeping one treasure safe, she must give up another.” It is at this point that Valmiki suggests that Sita write her own story as she is the most suitable person. And thus, Sita begins to write the Sitayan, her first-person account.

She reveals the events sequentially in a flashback, beginning at the point when Ram first came to Mithila to string Shiva’s bow – the Haradhanu – and consequently won her hand in marriage. Within this greater flashback, references exist to corollary stories such as how Shiva’s bow made its way to King Janak’s palace and the curse of Ahalya. They make the narrative richer and composite.

The author’s style is lively and engaging, egging on the reader. Also, Divakaruni excels in vivid descriptions, whether it is of a sari, the splendour of Ravan’s special chariot, the Pushpak or the passionate love-making between Ram and Sita after the latter’s rescue from Ravan. The couple’s intimacy is described thus:

“We made love in the moonlight, our limbs straining against each other. In my frenzy, I left my nail-marks on his chest. He bent my willing body into the positions that gave him most pleasure. Mad with love, we asked boldly for what we wanted and watched passion ripple across each other’s faces as we were satisfied over and over, only to crave the joys of love again. Our hungry bodies came together with an almost audible click, two halves that had been torn asunder reuniting. The elation of it was so immense that I thought I’d break into pieces and dissolve into the silver moonlight.”

Also, the language often has Hindi words like “pranam” and “sindoor” which lend a unique Indian flavour to the novel. Interestingly, dreams play a significant role in the narrative, enhancing its depth and scope. They foreshadow events that shift the course of the story and have a rippling impact on the lives of the characters. In essence, they effectively create a sense of foreboding. Sita’s inability to see or hear everything in her dreams compounds the suspense. This narrative technique brings a new dimension to one of the most popular Indian epics where the storyline is already well-known. It makes the novel a more compelling read.

Among the many narrative innovations, one of the most remarkable is the Pushpak changing its shape into a resplendent palace and carrying Ram, Lakshman and Sita to Ayodhya.

Here, Sita is not merely a dutiful, submissive woman as she traditionally appears. Similar to Draupadi in The Palace of Illusions (2008), she thinks ahead of her time and often along feminist lines. In many respects, she is a path-breaker. For instance, Sita argues with her mother about why custom demanded that Mithila be ruled by a man and not a woman. Later, on learning how Dasharath had taken one wife after another which gave rise to a sense of unhealthy competition, she is equally outraged. When Ram confesses to Sita that as a king, he wants to give every man a voice, no matter how humble his circumstances, she wonders about his preclusion of the women. At another point, she protests against Sage Gautam’s curse on his wife Ahalya. Refusing to blindly believe that Ahalya’s vow of silence was for spiritual merit, Sita interprets it as her way of punishing her husband for the grave injustice. However, compared to Draupadi in Divakaruni’s novel, Sita is far more calm, mature and strategic in her dealings. Nevertheless, she has foibles and failings, intense dilemmas and moments of weakness that make her relatable.

Ram is also portrayed with attention to delicate, realistic details. He is a kind, affectionate person and an ardent lover but becomes hostage to his desire to be the perfect king. His obsession with following royal duties often comes in the way of filial ties and ultimately leads him to an action that breaks his own heart as well as his beloved’s. Others such as Lakshman, Urmila, Kaushalya, Kaikeyi, Surpanakha, Ravan and Mandodari are depicted as round characters, with many facets to their personality. This makes the entire tale life-like and absorbing.

It is also creditable how certain practicalities are brought to the fore. For example, on her return to Ayodhya post exile Sita finds her quarters untidy and in disarray. It is because the queen mothers were too grief-stricken to attend to household details and Bharat and Shatrughna, along with their wives, had moved to the small town of Nandigram, refusing to enjoy any royal comforts till Ram returned home.

In a valedictory note, towards the end it is the Sitayan that Lav and Kush sing in Ram’s court, disobeying Valmiki who had taught the Ramayan and instructed them to sing the same. Divakaruni presents the boys as agents of change who sensitize the world to the suffering of women in general. Again, the ending is predictably different from the traditional Ramayan as Sita takes a stand, setting an example for women in the generations to come.

From time to time, the book explores the theme of love. However, it goes beyond mere romantic love to encompass parental love, sisterly love and other kinds of love born out of compassion and camaraderie. For instance, at one point Sita observes how love paradoxically weakens the strongest intellect at times when it is supposed to make one more courageous. At another point, she realizes how love sometimes follows a complicated course when Mandodari, Ravan’s queen is afraid to confide her guilty secret to him yet continues to love him deeply, despite the number of concubines he brought.

The author does full justice to the title of the novel as the forest and greenery form a strong motif. Sita feels an intense affinity towards flowers and plants and uses their healing properties to help ailing persons. Withering plants also respond to her touch and bloom beautifully. Even in her moments of peril such as during her abduction by Ravan and her captivity in Lanka, plants are shown to be empathetic towards her. Sita is also deeply attracted to forests and early on, admits that she wants to visit one someday even though it is a rare possibility in the life of a princess. Later, despite the hardships she has to endure during her forest exile, Sita marvels at the exotic trees and birds around her. Most important, she delights in the unique freedom the forest offers – which is out of reach in the confines of the palace. The forest is presented as an enchanted place frequented by wily rakshasas, shape-shifters and bird-like creatures with human heads. Subject to spells and magic, it is where the incredible can happen. Indeed, the forest occupies such a dear place in Sita’s heart that even after her return to Ayodhya, she instructs to have the grounds behind the palace made like a little forest.